Cooum River Restoration Boosts Chennai’s Urban Water Sustainability

Chennai’s Cooum River is undergoing a ₹735 crore eco-restoration under Smart City and state programmes. The project includes sewage diversion, desilting, tree planting, and plans for public riverfront development, boosting water resilience and urban ecology.

The Cooum River, one of Chennai’s oldest and most historically significant waterways, is undergoing revitalisation through a comprehensive urban ecological restoration plan. Once a clean inland stream originating near Coovarasanpettai, the Cooum flows around 65 kilometres before emptying into the Bay of Bengal near Napier Bridge. Even though urbanisation has progressively modified its natural flow, the river in the present day is a main player in flood control, drainage, and new schemes for Chennai riverfront development under national and state initiatives.

Recently, the Cooum has been recognized by the Chennai Rivers Restoration Trust (CRRT) as a priority area in the city's integrated water management master plan. With funding and administrative support from the Government of Tamil Nadu, and interdepartmental cooperation involving the Water Resources Department (WRD), Greater Chennai Corporation (GCC), and Tamil Nadu Urban Habitat Development Board, the river is being restored as a natural resource and as an urban resilience resource. The process of restoration fits into the other initiatives under the Smart Cities Mission and National River Conservation Plan (NRCP).

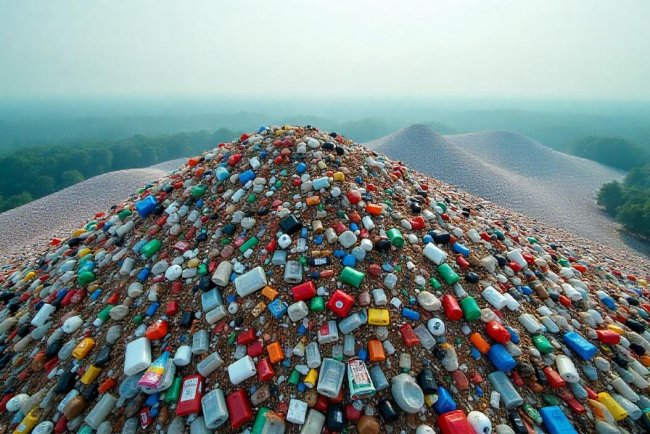

The focus of the efforts is placed on the Integrated Cooum River Eco-Restoration Plan to cover almost 32 kilometres of the river's urban course. Key areas include systematics for sewage diversion systems, desilting, removal of plastic wastes, interceptor drains, eco-friendly embankment building, and indigenous tree planting. Public amenities like pumping stations, fencing, and riverbank walks are also being constructed for easier access, security, and public interaction.

Conservation efforts are also combined with planned resettlement programs to move families residing in risk areas along the riverbank. More than 13,000 squatter settlements have already been removed from sensitive areas. Tamil Nadu Urban Habitat Development Board is partnering with communities for safe relocation and rehabilitation support.

WRD also recommended new flood mitigation infrastructure such as stormwater culverts and elevated canal banks. These are designed to make Chennai more ready to face high water events, particularly the northeast monsoon when the city is susceptible to flash floods. The natural alignment of the Cooum with major canal structures makes it important for stormwater outflow and the avoidance of urban waterlogging.

Community involvement has been fostered through school initiatives and clean-up events. These efforts, backed by local NGOs, complement government work by boosting civic responsibility and river stewardship. Citizen science activities are being implemented to assist with water quality and biodiversity trend monitoring on the improved segments.

The ecological impact of the Cooum’s restoration is expected to mirror the success seen in Chennai’s Adyar River project, where local fauna count increased significantly following habitat restoration. In the Cooum's case, CRRT has undertaken similar greening activities, with more than 60,000 saplings already planted. This afforestation effort will contribute to microclimate regulation and increased biodiversity in the river corridor.

One of its long-term urban planning, riverbanks are being made open to the public on environmental research subject. Suggested are pedestrian walkways, cycle tracks, gardens, and ecotourism complexes. It seeks to convert the Cooum into an open common good that is not only sustainable but also re-creative. Already suggested by the government is a Sailors Academy and boat launching stations along the river mouth, which are being developed under the Sustainable Urban Transport plan.

Nationally, India's Ministry of Jal Shakti has identified 351 stretches of dirty rivers in the country, a figure that underscores the necessity for waterway rejuvenation as a matter of urgency. City rivers such as the Bharalu in Guwahati, Mutha in Pune, and Musi in Hyderabad also suffer from such issues. Rivers become drainage corridors with the level of urbanization because of increased runoff, untreated sewerage, and encroachments. Solving these problems requires a three-pronged approach of infrastructure expansion, public consciousness, and ongoing surveillance—something that is available in Chennai today.

The Cooum also symbolizes the larger truth that city rivers are essential assets in India's freshwater economy. While big rivers like the Ganges and Yamuna get national attention, medium rivers running through expanding cities are just as vital. They drain not only stormwater but stabilize local climate, recharge groundwater, and maintain city-level biodiversity. Since India's urban population in 2036 is likely to be 600 million, the environmental health of urban rivers will be in the focus of climate adaptation and public health.

Chennai’s investment in the Cooum fits into the Smart Water Resilience vision, which includes real-time monitoring systems, data dashboards for flow tracking, and integrated sewage treatment frameworks. Sensor-based management tools are now being tested to assess sediment load, flow velocity, and flood risk in critical zones. The use of satellite mapping and GIS data has enabled planners to make location-specific decisions about river morphology and encroachment removal.

Institutional and legal control has also been reinforced. The National Green Tribunal has requested that there be quarterly reports on the restoration of Cooum, Adyar, and Buckingham Canal. This has created more accountability and inter-agency cooperation. Chennai water managers are also adopting best global practices, for example, the restoration of Cheonggyecheon stream in Seoul and the Isar riverbank style in Munich.

The revival of the Cooum River as an urban boulevard fit for the future is a showcase of the potential of integrated planning. Combining infrastructure renovation, biodiversity restoration, community engagement, and future tourism potential, Chennai transformed the Cooum into a climate buffer and public space. This project is a case study of river governance in Indian cities—where heritage, resilience, and sustainable futures meet.

Source

Chennai Rivers Restoration Trust (CRRT) and Government of Tamil Nadu reports

What's Your Reaction?